Political news is dominating the front pages right now, with a presidential election in the US, general election in Australia and a referendum in the UK. What does it all mean for markets?

“It promises to be a nervous week for global markets as traders mull over the relative performances of the US presidential candidates. With no clear favourite, the US stock market is unlikely to find any clear direction until the winner is named.”

Does that sound familiar? That line from an article by the Reuters news agency was carried in newspapers around the world. Last week? Last month? No. In fact, that article is from September, 1988 and was about the Bush-Dukakis debates of that year.1

As in the 2016 campaign, that election pitted two non-incumbents against each other as President Reagan completed his requisite two terms. As 1988 began, the New York Times/CBS News Poll talked of a political mood of “drift and uncertainty”.2

This isn’t to imply that every campaign is the same, but it does serve as a reminder that markets regularly navigate political uncertainty. As for supposed “patterns” in election years, research shows 12-month results are strikingly similar to overall averages.3

Of course, the US is not the only country holding national elections or referendums this year. So is Australia, where, again, two party leaders with no experience of leading a campaign are vying for a lower house majority in a race which pollsters say is too close to call.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, leading the Liberal-National Coalition, and Bill Shorten, leading the opposition Labor Party, are standing on diametrically opposed platforms—the former promising corporate tax cuts and the latter more spending on health and education.

In the Philippines, a new president and self-declared “strongman”, Rodrigo Duterte, has come to power advocating extra-judicial killings to stamp out crime and drugs.

And in the United Kingdom, voters are due on June 23 to cast a ballot in a referendum on whether Britain stays in the 28-member European Union. The UK conservative government has warned voters of a possible recession should they opt for a “Brexit”.

What do all these events mean for equity markets, for government bonds, for commodities and for currencies? Those kinds of questions get a real workout at these times in the financial media, which inevitably finds a wide divergence of opinion from market observers.

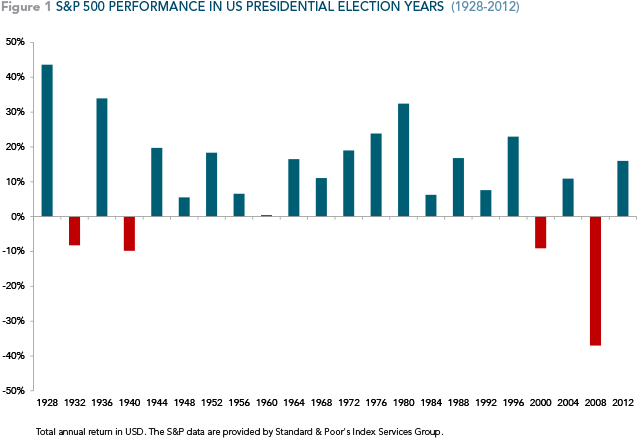

While many people will have a keen interest in political outcomes, academic studies show little pattern in actual market returns during US presidential election years. Figure 1 shows the performance of the S&P 500 in 22 US election years dating back to 1928.

You can see in four of those years, the market fell. In the other 18 instances, it rose. But the truth is this sample size is too small to make any definitive conclusions. And, in any case, it is extremely hard to extract the political from other influences on markets.

For example, the worst annual market outcome during a US presidential year in this sample was 2008 when Democrat contender Barrack Obama defeated Republican nominee John McCain. But if you recall that was also the year of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the global financial crisis.

Another down year for the market was 2000, the year Republican George W Bush defeated Democrat Al Gore in a tight contest. But that was also the year of the collapse of the bull market in technology stocks, the so-called “tech wreck”.

The point is that any one time markets are being influenced by a myriad of signals and events—economic indicators, earnings news, technological change, trends in consumption and investment, regulatory and policy developments and geopolitical news, to name a few.

So even if you knew ahead of time the outcome of an election in one country, how would you know that events elsewhere would not take greater prominence for the markets?

Keep in mind, also, that elections have a limited range of possible outcomes—a clear win for candidate or party ‘A’ or ‘B’, or an inconclusive result. Markets will adjust ahead of time to deal with risks around these outcomes. And the degree to which they move on the result will often depend on how much it varies from the consensus expectation.

So while we have responsibilities as citizens to take an interest in elections, it is by no means clear that these events have long-term implications for our decisions as investors.

That is much more a matter of our own goals and risk appetites, our investment horizons, the structure of our portfolios, our degree of diversification and the costs we pay.