When hedge fund legend Howard Marks from Oaktree Capital wrote a book on investing he devoted a chapter to the importance of being attentive to cycles. Marks said he lived by a rule that most things would prove to be cyclical. He went on to say that some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss would occur when other people forgot this rule. This message could well be applied in 2018 to emerging markets, where stock markets have delivered extraordinary gains on the back of a cyclical upswing in earnings. The earnings growth of 24 per cent in emerging markets was fuelled by strong domestic economic growth and favourable exports. Data shows that Asia had some of the strongest-performing stock markets in world in 2017 with emerging market economies Vietnam, India, Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia leading the pack.

Retail and institutional investors obviously felt good about the prospects for companies in emerging markets last year, judging from the data showing total inflows of $US85.5 billion in 2017. But when you combine the funds flow data with the latest outlook for emerging market earnings there are reasons to be cautious, according to Jonathan Garner, chief Asia and emerging market strategist at Morgan Stanley. He echoes Marks when he says investors need to be aware that economic and earnings cycles are turning. First, he notes that the cumulative number of positive weekly fund flows into dedicated emerging market funds (ex-China A-share funds) in the 10 weeks leading up to the end of the 2017 was the strongest since 2010.

Slower earnings forecast

He says that when you match the flows up against the Morgan Stanley base case for 2018 earnings for companies in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index there is reason to be cautious. Asian countries included in the MSCI EM Index include China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand. Countries outside of Asia include Russia, Brazil, Turkey, Colombia, Egypt, Greece, Poland, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, the UAE and Qatar. Garner says earnings for companies in the MSCI EM Index are forecast to more than halve this year. Earnings were 24 per cent in 2017 and are forecast to be 11 per cent in 2018 and 7 per cent in 2019. The strong earnings in 2017 help explain why the MSCI EM Index rose 36 per cent over the past 12 months.

One of the big reasons for the earnings drop in 2018 is because of the end to the bullish global cycles for NAND and DRAM memory chips. Morgan Stanley says these cycles will turn in 2018 because of oversupply. Both products have been in upward cycles since January 2016. The IT sector makes up about 28 per cent of the MSCI EM Index compared to about 16 per cent for the MSCI World Index. A sell-off in IT stocks in emerging markets that began in November has abated. Another valuation measure that Garner says is sending an amber warning signal is the price to sales ratio for emerging market stocks. This ratio is calculated by dividing the company’s market cap by the revenue in the most recent year.

Turning cycles

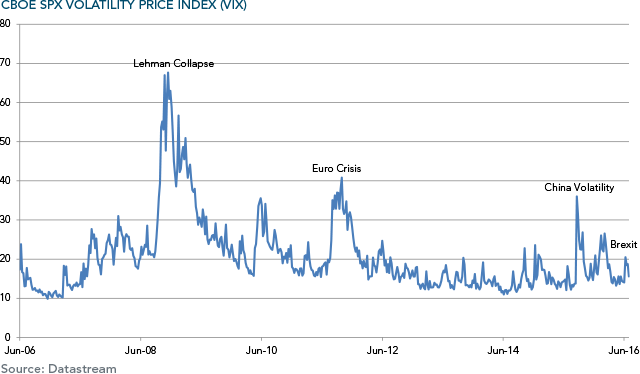

Garner says the price-to-sales ratio for emerging market stocks in the Asia-Pacific ex-Japan and ex-financials is higher than the 90th percentile relative to their 20-year history. The most interesting aspect of this analysis is to look at what happened to the performance of stocks when the cycle turned. The four previous high average price to-sale ratios were between December 1993 and September 1997 (1.8), December 1999 and September 2000 (1.6), September 2007 and May 2008 (1.75) and December 2010 and January 2011 (1.41). In the subsequent four years after the May 2008 peak the index fell 4.5 per cent. After other peaks it fell 2.5 per cent and 1.5 per cent and on one occasion rose 1.3 per cent. The message is that the turn in the cycle could lead to sub-par returns in the years ahead. Other reasons for caution are the higher oil price, which tends to hurt emerging markets more than developed markets, the low volatility as measured by the VIX.

Index, the buoyant IPO market in Asia and the low spreads between high-risk and low-risk bonds in the US market. Nevertheless, Garner and his colleagues in the Morgan Stanley equity strategy team in Hong Kong do recommend being overweight China, Brazil and India. They recommend being underweight Indonesia and Korea. The turn in the cycle in the oil market should be positive for energy stocks. The gap between price to book and price to sales ratios for semi-conductor manufacturers/tech hardware stocks and energy is at an all time high. But that should change in 2018.

Decelerating Chinese growth

Another cycle that has turned is the Chinese economic growth cycle, according to Garner. He says this is clear from the recent movements in the proprietary Morgan Stanley China Economic Index, which tracks electricity production, car sales, steel production, fiscal expenditure, real exports and real imports. Other economists predicting a deceleration in China’s GDP growth include Shuang Ding, the chief economist, Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered Bank. He has five key predictions for 2018. First, he says growth will decelerate to 6.5 per cent from an estimated 6.8 per cent in 2017 as the government pursues deleveraging and aims to reduce pollution. Second, CPI inflation will surprise on the upside at 2.7 per cent. Third, the People’s Bank of China will raise monetary operation rates by a total of 20bps, following the trend of monetary policy normalisation by major central banks. Fourth, the USD-CNY will reach 6.45 by end-2018, based on his assumption of a weakening US dollar. Finally, the debt-to-GDP ratio will continue to rise, but at a slow pace. The debt ratio is forecast to hit 277 per cent by the end of 2018, versus an estimated 270 per cent at the end of 2017.

Where to look

Those investors wanting to confirm their bullish bias toward Asian stocks should read the latest forecasts from HSBC for emerging markets and the buy recommendations from Japanese broker Nomura for the Philippines. Nomura is one of the few international brokers with a strong presence in the Philippines. Nomura says share price performance in the Philippines will depend upon earnings growth of about 13 per cent across the market in 2018. It is bullish in relation to Philippine banks, consumer discretionary, industrials and property sectors. Earnings growth for some of its buy recommended stocks are as high as 32 per cent and yet price earnings multiples are in the mid-teens. The consensus is that India will have the fastest-growing economy in Asia in 2018, which continues an upward cycle kicked off by the election of Narendra Modi in 2014. Garner at Morgan Stanley says the world’s institutional investors are overweight India but much less than they have been over the past few years. He expects real GDP growth to accelerate to 7.5 per cent in 2018 and further to 7.7 per cent in 2019, from 6.4 per cent in 2017.

“More importantly, we are confident that a recovery in private capex will be under way in 2018, for the first time in six years,” he says. Now that is a positive cycle to watch. Marks says that ignoring cycles and extrapolating trends are the most dangerous things investors can do.